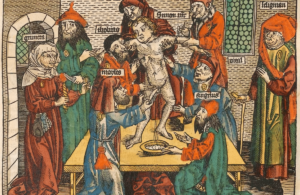

Woodcut of Simon of Trent (1472-1475), an Italian child whose death was blamed on the Jewish community in one of the most infamous blood libels.

Jews trace their ancient origins, as told by the Bible, to a kingdom called Judea on the shores of the eastern Mediterranean sea. They understood themselves as having been chosen by God to bear special customs and commandments that set them apart from other peoples. (In ancient times, many collectives had similar understandings of their distinctive origins).

Although there is evidence of hostility towards Jews even before the birth of Christ, much of the history of anti-Judaism can be rooted in the birth of Christianity out of ancient Judaism around the year 33. Early Christians had two reasons to be hostile to Jews: they blamed Jews for the death of Christ and condemned Jews for not believing in his divinity. (Jews do not believe that Jesus is the incarnation of God as told in the New Testament. Rather, Jews root their beliefs and practices in the Hebrew Bible, what Christians call the Old Testament). This stark difference in beliefs created competition and tensions between Jews and Christians, who each understood their own communities to be the true heirs to the words of the ancient prophets, and the others to be deeply mistaken.

In the year 70, not long after the death of Jesus, the center of Jewish life in the city of Jerusalem was destroyed by the Roman Empire. Jews ceased to have a specific political country, and instead fanned out across much of the Middle East and Europe. In the centuries that followed, Christianity gained popularity until it became the official religion of the Roman Empire, and the religion of many of the kingdoms of Europe that followed after the fall of Rome (around the year 476).

This means that for much of the Middle Ages (roughly 500-1500), Jews in Europe lived as a small minority within a larger Christian society. They were perceived as different and wrong in their beliefs and practices, making them visible and often vulnerable to popular hostility and state-sponsored violence. Yet Jews were also tolerated as long as they could accept a status that was inferior to the majority religions. They were often protected by royal rulers and church leaders and subject to distinct laws governing their residency, commerce and other privileges.

Jews were often suspected of plotting to harm Christians. In episodes known as blood libels, that usually occurred close to the Jewish holiday of Passover and the Christian celebration of Easter, Jews were charged with using the blood of Christian children to bake matzah. Blood libels occurred in many European cities during the medieval period. Similar sorts of fears about Jews also resulted in accusations that Jews caused the Black Death, a bubonic plague epidemic in the mid-1300s, by poisoning wells.

Between the 12th and 14th centuries, many European communities no longer wanted Jews to live among them at all. Jews faced massive expulsions from England, France, Spain, and parts of Germany. In places where they were permitted to live, they were often forcibly segregated from Christians into walled neighborhoods called ghettos.

Jews also continued to live in the Middle East in lands where Islam was the official religion. Here, too, Jews were protected by rulers and by the official religion, but were also subject to forms of discrimination and dislike on account of their religious and cultural differences.