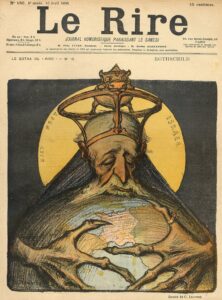

French antisemitic caricature portraying Jews taking over the world. The Rothschild Jewish banking family, often depicted in antisemitic propaganda, is shown having achieved world domination.

The nineteenth century, the dawn of the modern era in Western Europe, ushered in major changes in ideas about individual rights and citizenship along with the creation of nation-states. These changes increasingly made religion a private affair rather than the business of governments to impose and enforce. Across Europe, Jews were gradually granted citizenship and hence, no longer subject to previous restrictions in business, residency, and occupations. Therefore, Jews found new opportunities to participate in the social and civil life of the majority; many entered the emerging middle class, and a few enjoyed notable success. Liberal politicians, lawyers, and thinkers who proclaimed the importance of individual rights advocated for Jews to have the same opportunities as non-Jews, and were proud when their vision of a new society bore fruit. At the same time, even those who supported Jewish rights conveyed a clear message that Jews needed “improvement” in education and culture to be worthy of their newfound citizenship.

Others, however, saw the new opportunities presented to Jews as a symbol of a world changing too quickly. Modern antisemitic movements emerged as a direct response to the greater rights granted to Jews and the more expansive role they began to play in society. In fact, the term “antisemitism” emerged in Germany in the 1870s specifically to address the perceived “threat” of a newly emancipated Jewish population. Antisemites argued that greater Jewish rights had been a liberal scheme that allowed Jews to acquire power and status, and to displace and erode the foundations of Christian culture.

They focused their disillusionment on Jews specifically because Jews had benefitted visibly in these new systems and according to antisemites, had caused these changes through shadowy, conspiratorial means. Modern antisemitism encompassed a range of ideas, including nationalistic passions that posited that Jews would never be true patriots as well as systematized racial science—really pseudo-science—that identified Jews not only as culturally unassimilable but also as racially “other.”

This was an age that gave rise to conspiracy theories that imagined Jews as possessing secret means of controlling governments, even though no such systems existed. Such ideas, however, offered convenient explanations to those who felt left behind in a rapidly changing world. In an age of mass politics and new media (like the rapidly expanding newspaper industry) such theories circulated more widely and rapidly than ever before.

Although the Jews of Western Europe (England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Austria, Hungary) increasingly came to have the same rights as their non-Jewish neighbors, farther east, in the Russian Empire, Jews resided in a multiethnic empire where citizenship was not a prospect for any group. Nevertheless, authorities engaged in frequent campaigns attempts to “Russify” Jews sometimes by offering the “carrot” of education and other times through the “stick” of military conscription. In the Russian Empire, Jews (and other groups) faced restrictions about where they could live and what jobs they could hold. In an era of economic decline and demographic growth, many Russian Jews chose to emigrate to the West, seeking opportunities for themselves and their families in the United States. Others joined a range of revolutionary movements in Russia in pursuit of better future. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a series of pogroms—sporadic episodes of anti-Jewish violence—erupted in Russia, often in the wake of revolutionary upheavals, decimating Jewish property and resulting in loss of life. After the revolutions, leaders in the newly-created Soviet Union often formally condemned antisemitism. The Soviet state offered Jews unprecedented rights and opportunities that they eagerly embraced, though it thwarted the development of Jewish culture.

The United States attracted Jewish immigrants in significant numbers beginning in the midnineteenth century, and those numbers swelled to about three million with the arrival of Jews from Eastern Europe. Unlike the countries of Europe, the United States did not possess a medieval past and a long history of Jewish discrimination. While the US Constitution offered Jews expansive rights and freedoms, Jews faced a range of discriminatory policies in individual states. Moreover, U.S. immigration policies gave preference to Western Europeans and purposely restricted those from Southern and Eastern Europe.

This meant that the large number of Jews from the Russian Empire—along with Italians, Poles, and Slavs—were deemed undesirable and they were not considered “white.” In yet another example of the “inbetweenness” of Jews, they fared better than Asians, Brown and Black people, but remained excluded and unwelcome in other ways.

Certain attitudes toward Jews prevalent in Europe took on new dimensions on American shores, particularly the notion that Jews were not loyal patriots, that they fostered political and economic corruption, and supposedly threatened to take over certain sectors of the economy. Even after Jews joined other hyphenated Americans— such as Italian-Americans and Polish-Americans—in being regarded as white ethnics, the specter of Jews as particularly dangerous due to their supposed intent to dominate, exploit, and conspire lingered through the Red Scare, the Great Depression, the McCarthy era, and beyond.

The racial pseudo-science of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century affected Jews on both sides of the Atlantic. Racial scientists argued that Jews possessed distinctive racial qualities that made them detrimental and even dangerous to society. Particularly in Europe, political parties made ending Jewish civil and political rights a central platform of their campaigns, and gained increasing support.

This form of “political and racial antisemitism” reached a murderous peak with the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. Germany had been humiliated after the loss of the First World War (1914-1918). Facing severe economic hardship and political dejection, many Germans were receptive to ideas that promised to rejuvenate the German nation, and such programs often placed the blame for their hard times upon a scapegoat: the Jews. Mingling conspiracy theories with pseudo-science and an appeal to German pride, the Nazi party, led by Adolf Hitler, propagated ideas, founded organizations, and instituted policies designed to isolate Jews, with the goal of bringing them to economic ruin and forcing them out of Germany.

These ideas and organizations sufficed to attract sufficient numbers of supporters to lead to Hitler’s party winning democratic elections and becoming the dominant political party in Germany in 1933. When Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, he enacted policies that discriminated against anyone of Jewish “blood,” removing them from gainful employment, and revoking their rights. As Germany grew more powerful, Hitler launched a campaign to conquer much of Europe in the name of German dominance and Aryan racial purity, targeting Jews as well as other groups considered racially, mentally or physically inferior. In the Second World War (1939-1945). Hitler’s Nazi empire grew to control almost all of Europe, making possible not only the persecution of Jews but also the attempt to remove them first from Aryan society and ultimately from the world entirely. The Nazi party, and allied governments across Europe, implemented a process by which Jews were stripped of all of their possessions by law, removed from their homes, and relocated in crowded ghettos where many perished. As the Nazi campaign escalated, some Jews were shot en masse, and others sent to forced labor camps. Those who could not provide useful labor were designated for death camps. Some six million Jews were murdered during these years, an event now known as the Holocaust. By the end of the Holocaust, only one in three Jews remained from their former population.

In modern times, Jews have rebuilt and founded new homes and communities in Europe, South America, and especially in the United States. Three years after the end of WWII, the state of Israel was created, fulfilling the hopes of those Jews who embraced the Zionist movement, a political movement whose aim was to establish a national home for Jews. Zionism had gained momentum particularly in European Jewish communities in the decades before the war, and its goals became particularly urgent during and after the war itself, when many Jews were refugees without places to go or return to after the Holocaust.

In the years following the 1948 war, centuries of Jewish life in Arab states throughout the Middle East also came to a painful end. In the 1940s, approximately 900,000 Jews lived in countries like Iraq, Morocco, Syria, Algeria and elsewhere in the region. But the war escalated anti-Jewish tensions and violence in Arab nations, ultimately leading virtually all Jews in the region to leave, many of them relocating to the state of Israel.

For many Jews, the creation of Israel marked a new era of hope, safety and security. But the state also exacerbated tensions in the region and led both to political challenges and to new expressions of antisemitism that did not exist before Israel was founded. Distinguishing antisemitism from anti-Israel or anti-Zionist rhetoric has been a source of protracted debate and consternation. Without question, the very fact that Jews came to wield the power of statehood has altered the terms that defined Jewish experience in previous centuries, bringing about new historical circumstances and formidable challenges.

Today, Jews reside in fewer places in the world than they did a few centuries ago. In those places, they live in relative comfort and security, generally free from legal forms discrimination and persecution. Yet, the long history of religious discrimination, political inequality, and violence has left Jews collectively with painful memories and deep-rooted fears. Moreover, antisemitic tropes have proven resilient, particularly in times of crisis and discord, and they endure to the present day.

French antisemitic caricature portraying Jews taking over the world. The Rothschild Jewish banking family, often depicted in antisemitic propaganda, is shown having achieved world domination.

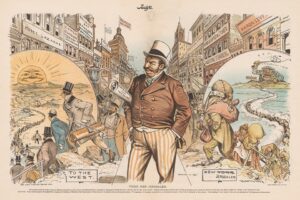

This cartoon depicts fears that Jewish immigrants were taking over New York City, turning it into a “New Jerusalem.” The Judge, July 22, 1882.

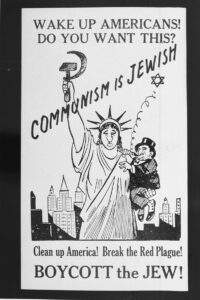

American antisemitic poster equating Jews with communism. The alleged communist conspiracy is depicted as transforming the Statue of Liberty into a Jewish figure. United States, 1939.

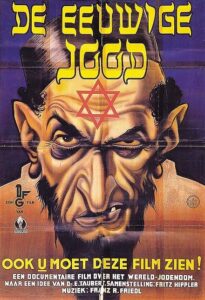

In 1940, the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda sponsored the production of the film Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) that portrayed Jews as alien to German culture, spreading disease and corrupting the nation.

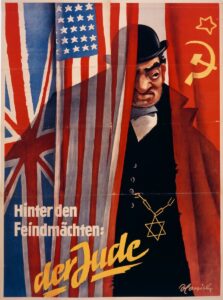

Nazi Propaganda, “Behind the Enemy Powers: The Jew.” Nazis often identified Jews as the power behind their enemies, supposedly creating wars and causing conflict for their own gain.