Dearborn Independent, May 22, 1920. Henry Ford used his newspaper to spread antisemitic ideas of Jewish conspiracy in the United States and around the world.

Today, antisemitism is often fueled by conspiratorial thinking—the fear that one’s life and fortunes are being controlled or manipulated by a secret and powerful elite.

As discussed above, these fears about Jews have existed since the Middle Ages, when Jews were suspected by Christians of secretly plotting to harm them, and such suspicions frequently led to the persecution and execution of Jews. In the modern age, anti-Jewish conspiracy thinking found its ways into documents like the fabricated “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” first published in Russia in 1903, that claims to reveal a Jewish plot to take over the world. The forgery has been remarkably durable. Automobile magnate Henry Ford circulated it worldwide in his publications in the 1920s and antisemitic radio priest Charles Coughlin excerpted it in his newspaper in the 1930s. The Protocols continues to be circulated to this day. It resurfaced after 9/11 in conjunction with nefarious claims that Jews must have been behind the attacks. This represents just one example of the persistence of the idea that Jews are secretly plotting to weaken, enslave, or destroy non-Jews.

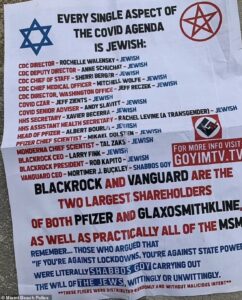

The continued power of such conspiracy thinking also emerged during the COVID pandemic when a significant number of people around the world, Christians, Muslims and others, came to believe that the pandemic was a Jewish or Israeli plot to harm non-Jews. According to one study, at the height of the pandemic, 20% of people in Great Britain believed that COVID was a Jewish conspiracy. As recently as 2022, leaflets were distributed in the Miami area with a Star of David and the slogan, “Every single aspect of the COVID agenda is Jewish.” Versions of these flyers also appeared in many other American cities.

The connection between conspiracy thinking and antisemitism is part of what distinguishes antisemitism from other forms of racism. Although it often includes caricature of supposed Jewish physical traits, antisemitism is not only based on the perception of physical difference like skin color but focuses more consistently on alleged character traits—cheapness, greediness, lecherousness, vengefulness, and more. One of the most widespread accusations against Jews today is that they are rich, powerful, conspiratorial, manipulative and untrustworthy.

Since the 2010s, antisemitic ideas and tropes have become more visible in American society, and experts have tracked an increase in the number of antisemitic hate crimes. One of the more potent recent antisemitic claims, partially borrowed from Nazi thought, is that Jews are trying to wipe out and dilute the purity of the white race, seeking to replace whites with other races and peoples. Two examples illustrate this point powerfully. In 2017, when a group of white Christian nationalists who were upset about the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee descended upon Charlottesville, Virginia, they chanted slogans like “white lives matter,” “blood and soil,” and “Jews will not replace us.” The following year, in 2018, the shooter at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh targeted a Jewish house of worship. But according to his own social media posts, what had set him off was that HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, had held a meeting at that congregation. In his rants on social media, he said, “HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people. I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered.”

These two incidents testify to the persistence of antisemitic beliefs that Jews are somehow plotting to undermine white dominance. They also demonstrate that while aspects of antisemitic thought are indeed distinctive, antisemitism remains deeply intertwined with hatred directed toward other groups—people of color, immigrants and “others”—who are perceived as unsettling the foundation of white Christian America.

At the same time, contemporary antisemitism derives from developments that take place far beyond American shores. Since the creation of Israel, events in the Middle East have precipitated fierce debates both within the American Jewish community and between different Jewish constituencies and many other groups. In the 21st century, disagreements over Israel and Palestine have sometimes included antisemitic tropes about Jewish power and conspiracy. One of the most vexing struggles in recent years is how to allow for legitimate debates and critiques of Israel while also keeping antisemitic stereotypes and canards at bay. Sometimes the lines between the two are clear and obvious, and sometimes they can be blurred or defined by individual opinion and outlook. This is one of the most challenging issues of our time.

In recent decades, experts have sought to define antisemitism in a way that distinguishes it from criticism of Israel while also acknowledging how the two can intersect with each other. Such experts agree that it is not antisemitic to criticize Israel in the way one might criticize any state or government for its actions— criticism of the Israeli government is common within Israel itself. However, criticism/protest against Israel verges into antisemitism when it uses the word “Zionist” as another word for “Jew,” when it denies or minimizes the Holocaust, when it treats Israel as the ultimate evil, or when it applies antisemitic tropes to Israel (e.g. treating Israel as a puppet master trying to control the world).

People disagree about where to draw the line between protest against Israel and antisemitism, but wherever you fall on that issue, it is important to bear in mind that calling for or legitimizing violence in the name of resistance to Israel has been used to justify attacks against Jews both within and outside of Israel.

Today, efforts to combat antisemitism are especially daunting. We live in an increasingly divisive and fragmented society that makes genuine communication and productive dialogue more difficult than ever. We desperately need better ways to talk to people with whom we disagree without demonizing them and resorting to stereotypes. The fact that information and ideas now circulate so often on social media only escalates the challenges, since the medium so often instills falsehoods in people’s thinking that are difficult to counteract and lends itself to impersonal, anonymous expressions of vitriol and hate. That is why we must focus on education, on fostering constructive methods of dialogue, and on the rights and responsibilities of building a civil society that values and protects all its members.

Dearborn Independent, May 22, 1920. Henry Ford used his newspaper to spread antisemitic ideas of Jewish conspiracy in the United States and around the world.

Antisemitic flyer distributed in Miami, Florida, falsely claiming that the response to the COVID pandemic was being orchestrated by Jews. January 2022.

Unite the Right Rally, Charlottesville, Virginia, August 12, 2017.